The Business of Sports

The economic reach of the Valley’s pro sports teams extends beyond the games

By Tom Gibbons

It’s a little past noon on a football Sunday, and there’s a wait at Jimmy Buffett’s Margaritaville restaurant in the Westgate City Center in Glendale, giving a visitor a few minutes to check out the seaside décor. Painted on the ceiling is a huge, fanciful nautical map that shows Los Angeles as an island, most of southern California under water and the shores of the Pacific lapping up against Glendale. Glendale would not be on the map, of course, if the eatery wasn’t located there.

And it’s likely there would be no map and no Margaritaville in Glendale if it weren’t for a couple of neighbors — the homes of the National Hockey League Phoenix Coyotes and the National Football League Arizona Cardinals.

The presence of the pro sports franchises has allowed specialty retail and an entertainment district to pop up in what six years ago were dusty fields by the Loop 101 freeway.

The Phoenix area is home to four major professional sports teams, one of 13 markets with all four. In addition, the Valley is one of just two markets in which no major teams share a venue. All four sports buildings have been built since 1992, with taxpayers footing most of the bill to the tune of more than $700 million.

The Valley of the Sun’s sports building boom mirrors a national trend that began in the early 1990s. Over the years, the projects here and around the country have come under increasing criticism. The costs are easy to tally, but what of the benefits to anyone besides the private businessmen who own the teams and the millionaire athletes they employ?

“That’s the price of admission,’’ says Barry Broome, president and CEO of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council. “Without pro sports, you’re not a top tier city.’’

Ray Artigue, executive director of the MBA Sports Business program at Arizona State University’s W. P. Carey School of Business, believes the benefits to the state and local economy are numerous, such as exposure for the area, branding and the tourist dollars that are brought in by pro sports. One of the strongest examples of pro sports’ economic impact is the Westgate City Center.

“Would something like that exist in Glendale without the sports teams?’’ Artigue asks. “I don’t think it would.”

To be sure, some development would have surfaced anyway in Glendale; after all, it’s flat land with freeway access. In the fall of 2000, when the final leg to Loop 101 was completed on the city’s West Side, Glendale was determined to get the right kind of development, something other than residential or generic big box stores.

Enter Steve Ellman, a developer who owned a money-losing hockey franchise and was trying to build an arena and entertainment venue. Ellman had been fighting with city leaders in Scottsdale to OK a deal to front him money that would be recaptured through sales tax in order to build his arena on the site of a defunct shopping mall. Ellman had twice won voter approval for his project, but it was obvious the Scottsdale City Council was going to make him go through a third election.

Ellman, chairman and CEO of the Ellman Companies, approached Glendale and worked out a deal in which the city committed $180 million for the arena and Ellman promised to build a retail, entertainment and residential district — Westgate City Center.

“There was substantial risk,’’ says Glendale Mayor Elaine Scruggs.

The hockey arena and the planned entertainment district paid off quickly, making Glendale a player in the race to land the site for the Cardinals’ new stadium.

“We could have bid before, but we didn’t have the amenities they were looking for,’’ Scruggs says.

Glendale won out. Jobing.com Arena and the University of Phoenix Stadium made Westgate more attractive to other businesses, such as outdoor equipment giant Cabela’s and Margaritaville, which is one of only six Margaritavilles in the country.

“This is a one of kind. There probably won’t be another one in Arizona,” Scruggs says, adding that businesses such as Margaritaville help make Glendale a destination.

“We’re very proud to have been the first team out here and an anchor for all the development that followed,’’ says Jeff Holbrook, the Coyotes executive vice president and chief communications officer.

Retired chairman and CEO of Swift Transportation, Jerry Moyes, is now the principal owner of the Coyotes and was a key investor when the team decided to set up shop in Glendale. He is also a longtime West Valley resident.

The Cardinals are taking a page out of the Coyotes’ development play book. The Bidwill family, which owns the Cardinals, has a development project in the works called cbd 101, which is on 77 acres just south of the University of Phoenix Stadium. The plans include a 35-story tower with residential, office and hotel space.

“This would be a signature feature for Glendale,’’ says Michael Bidwill, president of the Cardinals (see full story on p. 10).

The National Basketball Association’s Phoenix Suns with US Airways, and Major League Baseball’s Diamondbacks with Chase Field, have a similar effect on Downtown Phoenix, slowly transforming the area from a ghost town after 5 p.m. into a 24/7 hot spot that city leaders envisioned.

The Diamondbacks play 81 games a season downtown and the Suns play 41, plus playoffs.

“There are also the Mercury and the Rattlers,’’ ASU’s Artigue says, referring to the women’s pro basketball team and the Arena Football League franchise.

Pro sports events also provide a place for deals to get done.

“The Suns have pretty much become a must-go place for business deals,’’ Broome says.

The Suns have the AOT club for anyone who buys a floor-level seat. The 510 floor-level seats are all sold out at prices ranging from $400 to $1,700 a seat.

Suns President and Chief Operating Officer Rick Welts says the fans often wanted to meet other floor-level ticket-holders and discuss business. The AOT Club was created to give them a chance to meet and greet before and after the game.

“We have created the best business-to-business social network in the Valley, without question,’’ Welts says. “That’s the single most frequent comment I get from those people.”

The pro teams also bring in tourist dollars.

The Diamondbacks, for instance, drew 16 percent of their parties from outside of Maricopa County, according to a 2001 Maricopa County Stadium Commission study.

Then there’s the mega event of all — the Super Bowl.

“You’re looking at $400 million to $500 million in economic impact from one week,’’ Artigue says. “Of course, that’s an extreme example.”

And the teams give back to the community. The Diamondbacks, for example, gave $3 million through their foundation.

The teams are privately held and do not release financial information; however, it’s generally believed the Coyotes have been consistently unprofitable. With the smallest venue, the team also has the smallest attendance of the major Arizona pro teams, but its following is a devoted one. For many transplants from colder climates, a Coyotes game is a taste of home.

“Hockey is a game that sort of becomes ingrained in you,’’ says Holbrook, who came here from Buffalo, N.Y. “Hockey has really loyal fans.”

The Suns have been break-even or profitable. The Cardinals were believed profitable except for their last few years playing in Sun Devil Stadium in Tempe, when they drew around half the league average.

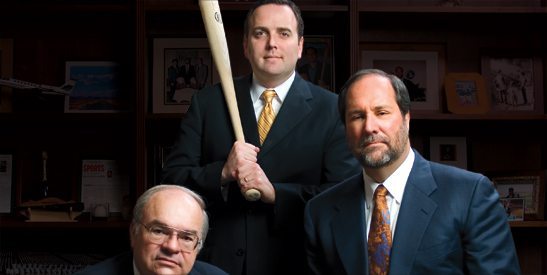

The Diamondbacks, who were brought to Phoenix by the Suns’ legendary former owner Jerry Colangelo, were winners on the field in their early years, taking the 2001 World Series, but they ran up massive finasncial losses. In 2004, after a series of clashes with the Diamondbacks’ four majority owners, Colangelo was ousted from the CEO chair. Under current managing general partner Ken Kendrick and general partner and CEO Jeff Moorad, the Diamondbacks have been profitable for the past three years, the executives say. Last year, the Diamondbacks were winners on the field as well. They led the National League in victories with 90 and went to the league championship series.

The Diamondbacks, who were brought to Phoenix by the Suns’ legendary former owner Jerry Colangelo, were winners on the field in their early years, taking the 2001 World Series, but they ran up massive finasncial losses. In 2004, after a series of clashes with the Diamondbacks’ four majority owners, Colangelo was ousted from the CEO chair. Under current managing general partner Ken Kendrick and general partner and CEO Jeff Moorad, the Diamondbacks have been profitable for the past three years, the executives say. Last year, the Diamondbacks were winners on the field as well. They led the National League in victories with 90 and went to the league championship series.

Moorad stressed that the team’s ownership sees running the baseball team as sort of a stewardship.

“Ownership hasn’t taken a penny out of this team,’’ he says, prompting Kendrick to add with a laugh, “Of course, for the first seven years, there wasn’t anything to take.’’

AZ Business Magazine March 2008 | Next: The Ground Game