As the number of Arizonans who have contracted COVID-19 has raced past 100,000, testing for the novel coronavirus that causes the respiratory disease has become a priority. Some of that testing now is being done through saliva, a process that’s easier and less expensive.

Arizona’s first COVID-19 saliva test – designed by scientists at Arizona State University to make university-wide testing feasible in the fall – already has been administered to more than 6,000 people, according to Vel Murugan, an associate research professor at ASU’s Biodesign Institute. It’s an alternative to nasopharyngeal swabs, which are uncomfortable and can be dangerous to frontline workers.

Saliva tests may be even more accurate than nasal tests, said Joshua LaBaer, executive director of the Biodesign Institute. Nasopharyngeal swabs involve inserting a cotton swab into the nose and pushing it to the back of the palate, where the sample is collected. The swab then is put into about half a teaspoon of liquid, mostly saline.

“But in the case of the saliva test, the entire sample is produced by the person,” he said. “So, if there’s virus in there, there’s probably a little bit more virus in the saliva test. So, in our hands, it’s as effective, and in at least a couple of cases it looks like it might be a little bit more effective.”

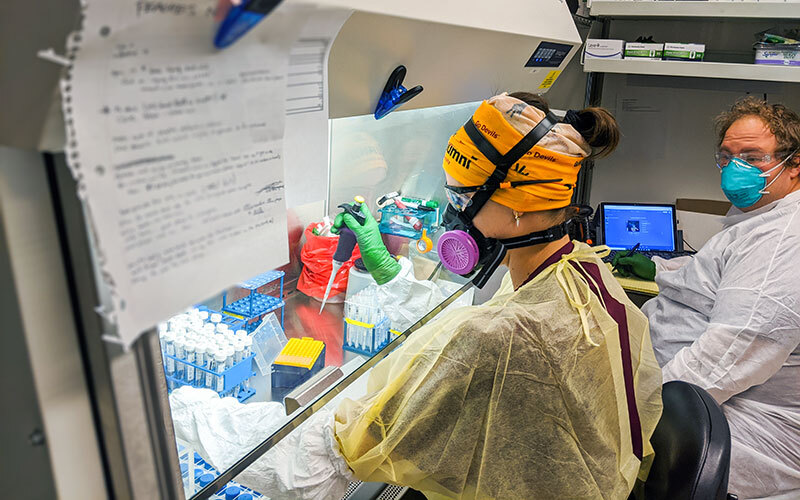

LaBaer said the saliva test simplifies sample collection because it doesn’t require a trained medical professional – the person being tested simply spits into a strawlike apparatus. The nasal test can cause sneezing and coughing, which can spread the virus to a medical professional, who must wear full body protection.

The saliva test doesn’t require full protective gear, and it can be done quickly and indoors, rather than requiring people driving up to a testing site to get the nasal swab. For both tests, the lab gets results one to two days after receiving the sample.

The saliva test does have limitations, according to Thomas Grys, the co-director of microbiology at Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. He said that the saliva test, like nasal tests, won’t always detect the virus if you have it.

“It could be in your nose, but not in your saliva,” Grys said, “or it’s in your saliva at a low level, such that the assay doesn’t detect it because it’s not sensitive enough.”

Grys said the Mayo Clinic helped ASU organize a testing lab and shared virus samples so that the university could make sure the test worked.

Although ASU doesn’t have the resources to do all of the testing, researchers are partnering with companies, charities and other organizations, including the Navajo Housing Authority. ASU provides testing kits and the training to use them.

Once samples are collected, they are inspected to ensure they were properly collected and that the substance collected was saliva. The samples then go to ASU, where they’re tested for the novel coronavirus. ASU, in partnership with the governor’s office and the Department of Health Services, is planning to open public testing sites.

“One of the advantages of the saliva test is that the samples are stable,” LaBaer said. “We’ve tested stability for up to four days if you keep them on ice packs.”

This means that out-of-state testing is an option. Researchers already are working with partners in New Mexico and have spoken to potential partners in California.

ASU’s saliva test is new to the state, but the concept isn’t new. Researchers in other states have developed saliva-based tests. ASU’s saliva test originally utilized a testing kit used by Rutgers University, which costs roughly $10, but LaBaer estimates ASU’s kit costs less than $1.

The saliva test will also help with testing students when they return to ASU campuses in the fall.

“We all felt that it was important that we had the capacity to test everyone if that became necessary,” LaBaer said.

David Harris, a professor of immunobiology and directs the Biorepository at the University of Arizona, has been working to develop and distribute collection kits for COVID-19 tests.

“You actually need a couple of tests,” he said. “You need the saliva or cheek swab to detect the virus to see if they have it, and if they don’t have it then you need an antibody test to see if they were immunized by the (yet to be developed) vaccination, and now they’re protected.”

Harris believes the practicality of the saliva test will help detect the fast spreading disease.

“The key here is, be able to do lots of tests, quickly, and repeatedly,” he said.

Testing is critical right now as COVID-19 cases continue to climb. The Arizona Republic reported people have contended with long wait times, supply shortages and fully booked providers. Instead of three to five days for results, some people have waited for several weeks.

So far more than 800,000 COVID-19 tests have been given around the state. On Monday, the number of positive cases reached 101,441.

Story by Nathaniel Boyle, Cronkite News