Before Interstate 10 was built, the Tohono O’odham Nation was relatively removed from the rest of southern Arizona.

DEEPER DIVE: 7 Arizona cities rank among Top 100 worst commutes in U.S.

But in the 1960s, construction on the cross-country highway skirted the edge of the reservation. According to one of the tribe’s elected leaders, it didn’t just bring noise and air pollution, it encouraged development around the once-quiet community.

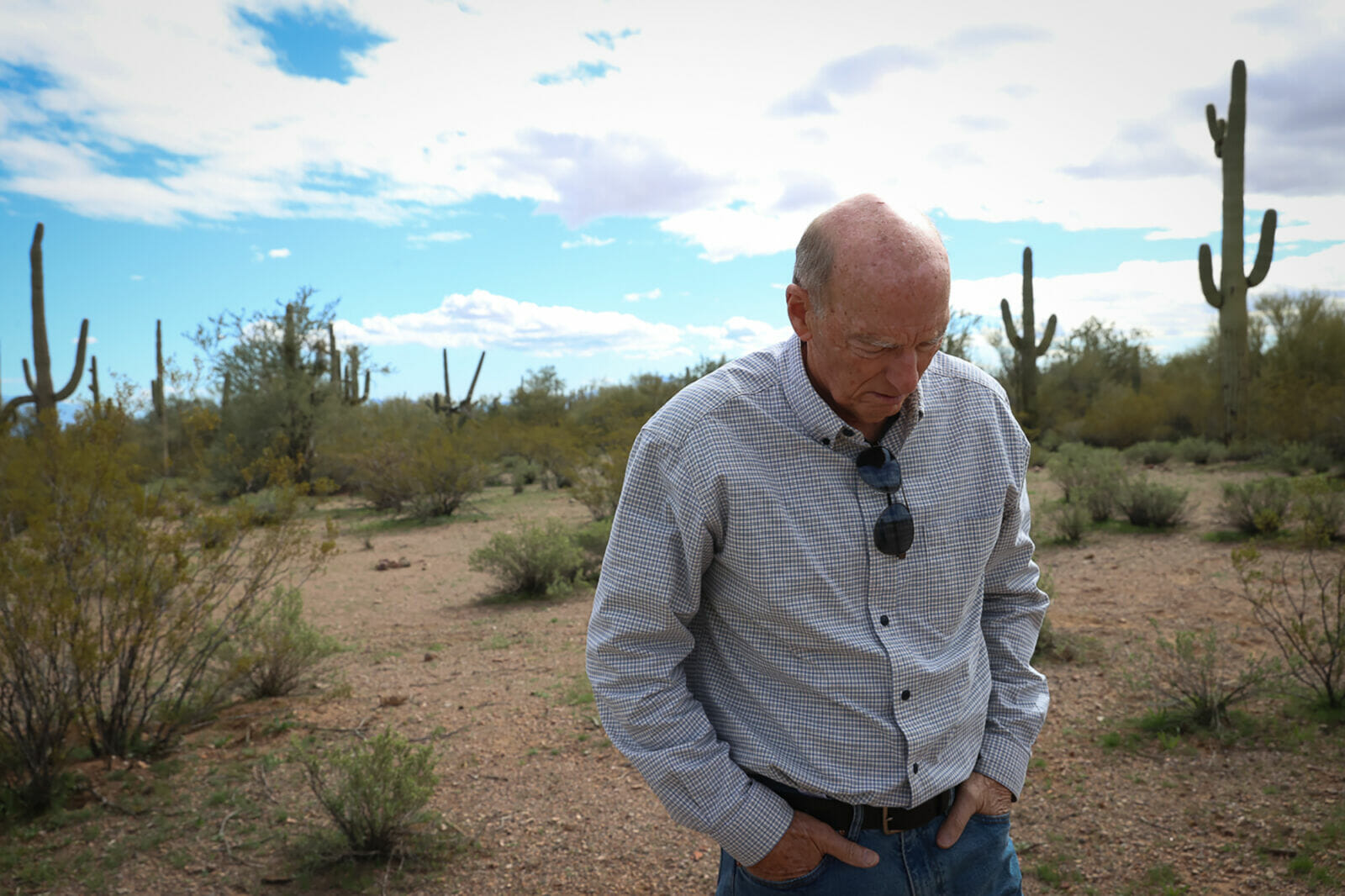

Austin Nuñez has been chairman for the Tohono O’odham Nation’s San Xavier District since 1987, or as he says, “a few years.”

Nuñez said when he was a child, downtown Tucson seemed far off in the distance, but that’s no longer the case.

“I mean, it’s right there, we’re just adjacent to the city of Tucson boundaries,” said Nuñez, whose district includes the historic San Xavier del Bac Mission.

As neighborhoods around the reservation expanded, there were more and more trespassers. One I-10 exit within the reservation led to nowhere.

“People would get off there and trespass on the desert and they’d sometimes take cactus or wood and we’d have to let them know that that was not allowed,” Nuñez said.

Eventually, Tohono O’odham leaders worked with the Arizona Department of Transportation to close the exit so travelers would be unable to access the reservation from the interstate.

Now, members of the Tohono O’odham feel threatened by another federal highway, this one a north-south interstate that would be built adjacent to their community.

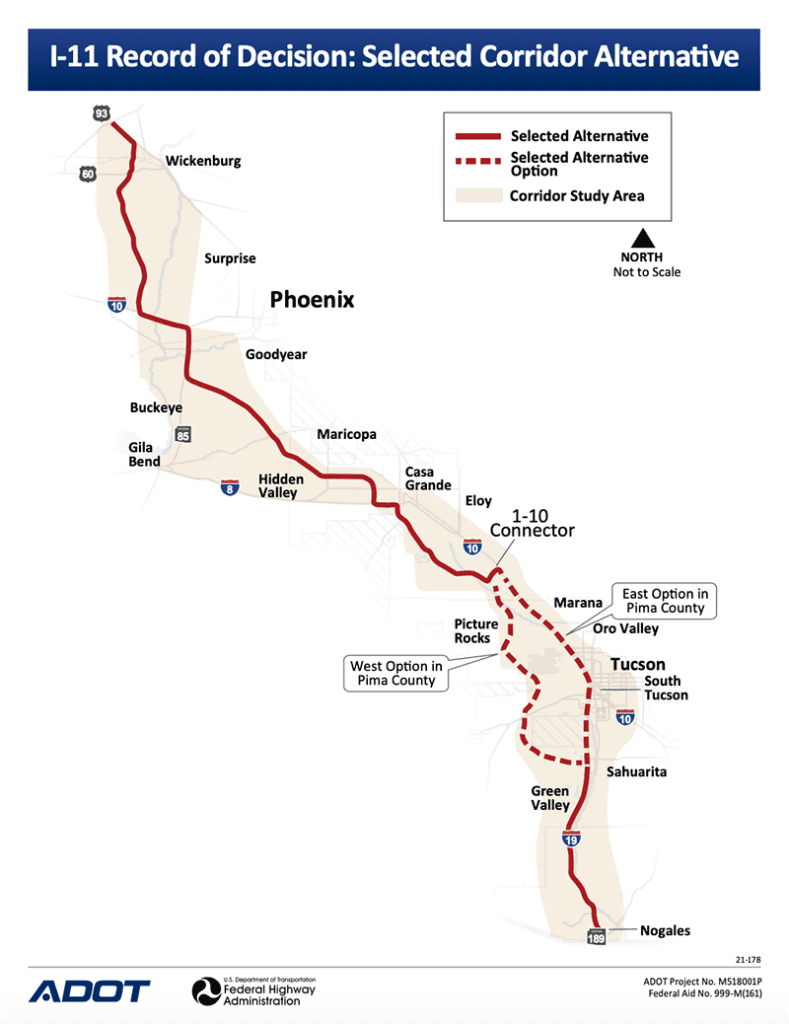

For the past decade, the Federal Highway Administration has been working on a plan to extend Interstate 11, which runs for 22 miles in Nevada and concurrently with U.S. Route 93 between Henderson, Nevada, and the Arizona state line. A proposed 280-mile extension from Wickenburg to Nogales would skirt the Tohono O’odham community.

Nuñez said the original plan called for I-11 to cut through a corner of the reservation.

“We told them ‘no,’ we didn’t agree with that,” he said. “They should keep that corridor as far away from us as possible.”

Even though the proposed path doesn’t go directly through Tohono O’odham land, Nuñez said it’s still a problem.

“We’re being intruded on,” he said. “There should be other alternatives that could be looked at that wouldn’t (include) construction” so close to tribal lands.

In addition to nearby I-10, a major electrical transmission corridor and natural gas line run through the Tohono O’odham Nation.

“The community just said, ‘We don’t need any more,’ ” said Nuñez, reflecting on the proposed I-11. “Anything we can do to prevent (another highway) would be the best thing for all of us.”

But some see economic benefits to expanding the north-south highway that could eventually stretch from Canada to Mexico.

Christian Price is the former mayor of Maricopa and chairman of the I-11 Coalition, a nonprofit advocacy group in favor of the highway.

“Phoenix and Las Vegas are really the only destinations in America with … over a million people that have no direct connecting freeway,” he said. “This would help move people. It would help goods and services be transported … and it is critical to a growing state like Arizona.”

Price said environmental impact studies have been completed to ensure the highway will take the best route.

But the proposed corridor would be built through Saguaro National Park, the Tucson Mountains and Ironwood Forest National Monument, which has drawn the attention of conservation groups.

In April 2022, the Coalition for Sonoran Desert Protection, Center for Biological Diversity, Friends of Ironwood Forest and Tucson Audubon Society filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Tucson over the proposal.

In the lawsuit, the groups allege that the Federal Highway Administration failed to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act, Section 4(f) of the U.S. Department of Transportation Act and the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1958.

They said the FHWA did not do its due diligence in assessing the environmental impact of the proposed highway.

Ironwood Forest National Monument has the densest stand of ironwood trees in the world, according to Tom Hannagan, board president for the nonprofit organization Friends of Ironwood Forest. He said it’s also home to the only indigenous herd of desert bighorn sheep in southern Arizona.

“We’d like to keep that herd as healthy as possible,” he said.

Along with desert bighorn sheep, there are desert tortoises, pygmy owls, lesser long-nosed bats and cactus wrens living within the monument.

Hannagan said the FHWA did not include Ironwood Forest National Monument in its environmental impact statement.

“They did not consider it as a recreational area, which it is,” he said. “They didn’t consider it as a wildlife refuge, which it is.”

Ironwood Forest National Monument also has as many as 3,000 archaeological and historical sites, according to Hannagan’s group.

After years of attending stakeholder meetings and submitting numerous complaints against the highway, Friends of Ironwood Forest saw only one option.

“We felt like the only thing we can do now is ask a court to intercede,” Hannagan said.

David Robinson, director of conservation advocacy and interim executive director at the Tucson Audubon Society, said there’s no way of knowing how many species would be impacted by I-11.

“We’re talking about destroying a huge swath, and then having the ripple effects out beyond them,” he said. “It’s all so interconnected. But it really would impact an entire desert ecosystem.”

Robinson cited the desert tortoise as one animal that could be harmed.

“There’s no way it’s crossing a freeway,” he said. “This sort of freeway would be an impenetrable barrier to land-based animals.”

He called the entire proposal misguided.

“Wherever they build, it is going to be damaging in terms of environment, in terms of human health, in terms of climate. This particular lawsuit is objecting to one of the two proposed routes that would go through really sensitive, really valuable desert habitat. We’re absolutely opposed to that,” he said. “The alternative route that would come closer to the city would have really bad impacts on human health. So we’re not in favor of that either.”

As for the development that the highway would inevitably encourage, Robinson worries how the desert could handle it.

“We can’t afford that development just in terms of water,” he said. “We don’t have enough water for things currently.”

The I-11 Coalition’s Price disagreed.

When asked if he thinks there is enough water to support new development in the area along the proposed corridor, Price said, “Oh, very much so. Arizona is about water in different areas. And one of the things that Arizona has done for a long time, is it’s planned for its water shortages.”

Part of I-11 would pass through the Lower Hassayampa Sub-basin, a groundwater aquifer in the far West Valley.

Ryan Mitchell, chief hydrologist and assistant director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said it’s not a simple yes or no to whether there’s enough water in the area to support new development.

The department issues certificates of assured water supply if there’s enough water for 100 years to support development. But not everyone with a certificate has started building.

“When we do our model, we can’t just look at who’s there pumping now, we have to also include any and all of those certificates that have been issued,” Mitchell said. “And as of right now, the results of our model when we project forward 100 years, is that there is unmet demand for those future planned communities … that are already over-allocated in the aquifer.”

That means there’s not enough water for more certificates to be distributed. But there are some undeveloped certificates for land near the proposed I-11 corridor.

“They could sell the property with the water rights and the analyses,” Mitchell said. “There’s a lot of stuff that people can do between now and whenever the highway is there and whenever it gets built.”

Robinson of the Audubon Society said there’s a better solution than constructing another highway.

“In terms of climate, this is about as backward thinking as you could get,” he said. “This is like a mid-20th century solution to traffic congestion, when we need a 21st century one. Rail is an obvious answer and that was dismissed as an alternative.”

Although he supports multimodal transportation, Price said there’s one crucial reason that it won’t work: money.

“Rail is very, very expensive, and so it’s actually cheaper and more effective to do a roadway,” he said.

On Jan. 26, U.S. District Judge John C. Hinderaker heard arguments in Tucson on a motion by the federal government to dismiss the conservation groups’ challenge to I-11.

Wendy Park is an attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity.

“The issue was whether certain claims challenging the highway administration’s failure to analyze the impacts on public parks and wildlife refuges should go forward, or should wait to be heard until after ADOT decides the highway’s specific alignment,” Park said in an email. “The highway administration failed to do that analysis over the objections of BLM (U.S. Bureau of Land Management), National Park Service and other agencies.”

According to Park, it could take anywhere from a few weeks to a few months for the judge to rule on the case.

If the highway administration is allowed to move forward, the Tohono O’odham’s Nuñez said his tribe may reach out to congressional leaders for assistance in stopping the project.

“It’s just undeveloped and looks beautiful,” he said. “We would like to keep it that way as much as possible.”

Author: Amber Victoria Singer, Cronkite News

Photo: Evelyn Nielsen, Cronkite News