Arizona is gearing up for the first-ever “Tier 1” shortage on the Colorado River in 2022, which will trigger significant cuts to the state’s annual allocation from its most important water resource.

As daunting as it sounds, the vast majority of citizens and businesses will not be affected, state water leaders said during a Colorado River Preparedness briefing last week.

Arizona is also well prepared to weather expected shortages the next few years, and is in the process of developing the next steps to protect and augment the river’s supplies as the drought persists, said the state’s top two water leaders. They held the briefing to update the public about what to expect, what the current conditions are and plans for the future.

“This is a day we knew would come at some point and we’ve been preparing for this moment for at least a couple of decades,” said Ted Cooke, general manager of the Central Arizona Project (CAP), the entity that delivers the river water to the populous dry inland deserts including metro Phoenix, metro Tucson and Pinal County.

“We have a plan. It’s called the Drought Contingency Plan, and we’re implementing that plan,” said Cooke, who held the briefing with Tom Buschatzke, the director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR).

One of longest droughts on record

The two seasoned water leaders have been shepherding Arizona through one of the longest, driest droughts on record.

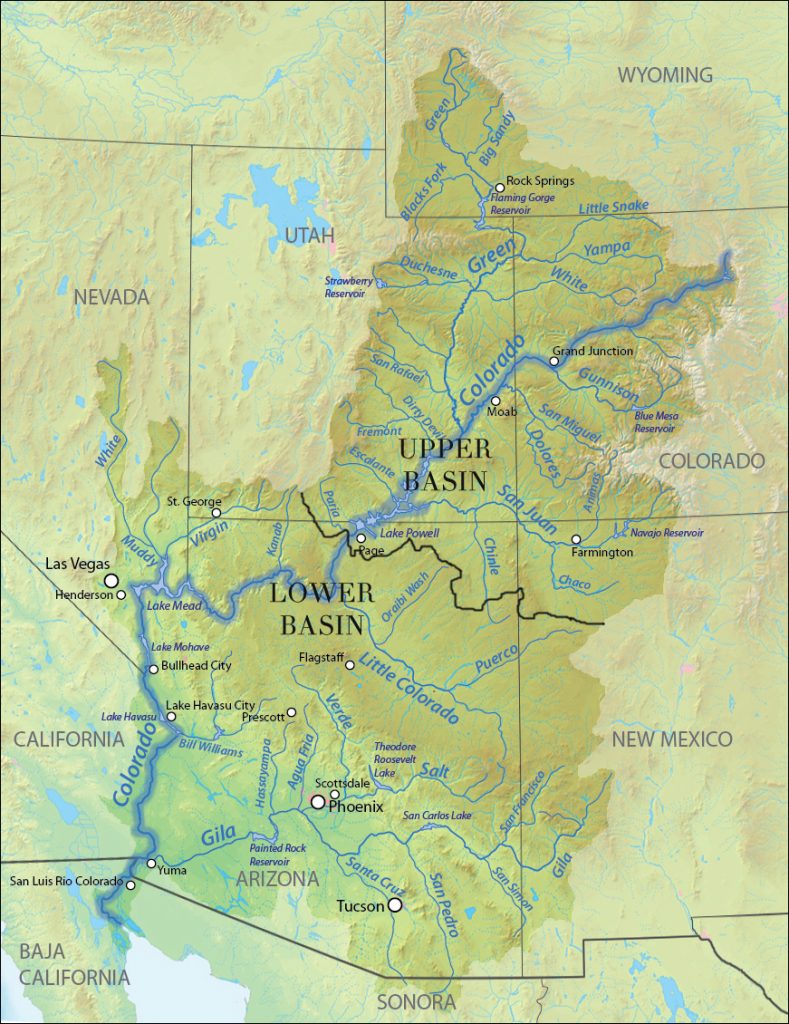

Now, in its 21st year, the drought is causing levels to drop at the Colorado River’s two “storage tanks” — Lake Powell for the upper states and Lake Mead for the lower states and Mexico. The Colorado River basin states that feed off the river are Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

Over the past two to three years, the drought has “intensified significantly,” said Daniel Bunk, chief of the Boulder Canyon Operations Office for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), who detailed the current conditions at the briefing.

As of April 26, Lake Powell was down to 35 percent full and Lake Mead, 38 percent. When combined with water storage in other facilities, the system storage is at 43 percent, almost 10 percent lower than last year, Bunk said.

READ ALSO: Here’s what is being done to protect Arizona’s water supplies for future growth

Based on the hydrology, it is “highly likely” that the BOR will announce a Tier 1 shortage for 2022. This would require Arizona to reduce its use by 18 percent, or a total of 512,000 acre-feet, borne almost entirely by the CAP system.

The results show a high likelihood of Tier 1 reductions in 2023 as well as an increasing risk of more drastic cuts with Tier 2 conditions in the near future.

Most severe cuts on central Arizona farmers and ranchers

Reductions will fall largely to central Arizona agricultural users, which have low priority rights when it comes to river supplies. Cities and tribes have high priority rights and will not be affected by a Tier 1 reduction. Tier 2 cuts would be more widespread among users in order to shore up levels at Lake Mead.

While cuts next year will be “painful,” mitigation efforts, including funding from public agencies, large corporations and nonprofits are lessening the blow, Buschatzke said.

Hardest hit, the agriculture industry in Pinal County received funding to install new groundwater infrastructure to help augment the loss of river water.

Agreement to leave water in storage lakes is working

The efforts came out of the historic Drought Contingency Plan passed by an act of U.S. Congress in 2019 to protect water levels in the two lakes. Arizona, the six other states, Mexico and the U.S. entered into the DCP, which mandates how water cuts will take place when the lakes drop to certain levels, or tiers.

Included in the DCP is a new water level, “Tier Zero,” for extra protection. Under Tier Zero, if the water level dips below 1090 feet above sea level, reductions are triggered to leave water in the lake. In 2020 and currently, Lake Mead has been in Tier Zero. A Tier 1 shortage occurs when Mead drops to 1075 feet above sea level.

In order to get the massive agreement sealed, public agencies, private corporations and NGOs contributed tens of millions of dollars to leave water in the lake for conservation projects and to provide aid to Pinal County farmers. Water users agreed to share some of the pain by either leaving water supplies in the lake or sharing excess water with others with lower water rights.

Because of the DCP, water supplies are now secure for the next few years, Buschatzke said.

“Together these efforts reduce the pain of the near-term reductions while addressing risks of future shortages,” he said.

Next challenge: finding new water supplies

Now, Buschatzke and Cooke are back co-leading the next drought plan negotiations.

They are co-chairing a statewide committee, the Arizona Reconsultation Committee, to start hammering out Arizona’s part of new DCP guidelines in 2026.

More substantial cuts could be on the horizon. Pressure is on to build new infrastructure to conserve water and find other supplies beyond the river to relieve the burden on “America’s Nile.”

For additional information and updates about Arizona water efforts, visit: new.azwater.gov or www.cap-az.com.

This story was originally published at Chamber Business News.