Arizona’s economic recovery from the pandemic gained significant momentum in the second quarter. Job gains surged, housing permit activity remained very strong, and taxable sales remained on track for significant gains. The housing market grew even hotter in the second quarter, with low inventories, high construction materials prices, and strong demand driving median home prices up by 30% or more in June. Federal fiscal stimulus is gradually dissipating, but income gains are likely to remain robust this year as the labor market continues to recover.

READ ALSO: Silicon desert: The rise of fast-growth Arizona firms

The baseline outlook calls for Arizona jobs to regain their pre-pandemic peak in the fourth quarter of 2021, assuming the COVID-19 vaccines remain effective against emerging variants and that vaccination progress outpaces the outbreak. The pessimistic scenario assumes less progress against the virus and thus a slower recovery. Under this assumption, Arizona jobs regain their prior peak in the first quarter of 2022. The optimistic scenario calls for state jobs to regain their prior peak in the third quarter of this year.

Arizona Recent Developments

Arizona posted another month of strong job gains in July, with a seasonally-adjusted increase of 21,100. The strong gains in June were revised up to 40,300.

As of July, Arizona has replaced 93.7% of the jobs lost from February to April of last year, which left the state 20,900 jobs short of the prior peak. The nation has replaced 74.5%. Since June of last year, Arizona has added an average of 12,800 jobs per month. If the state can maintain that pace, we will be back to the pre-pandemic peak in September. If we return to average monthly job growth during 2015-2019 (6,300 per month), then we will regain the pre-pandemic peak in November. Arizona is currently on pace to regain our prior peak well before the U.S., which would accomplish that in April 2022 (at the pace set since last June).

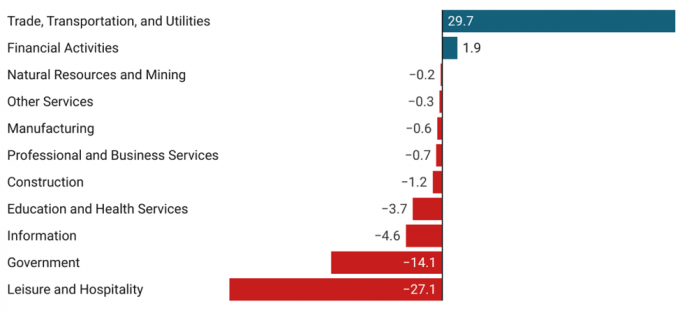

Jobs in most major industries in Arizona remained below their pre-pandemic peak in July (Exhibit 1). Leisure and hospitality and government were the furthest behind, followed by information and education and health services. Trade, transportation, and utilities has added by far the most jobs since February 2020, followed distantly by financial activities.

Exhibit 1: Arizona Jobs by Industry, Change From February 2020 to July 2021, Seasonally Adjusted, Thousands

The state’s seasonally-adjusted unemployment rate fell to 6.6% in July, down from 6.8% in June. That was above the national rate of 5.4%.

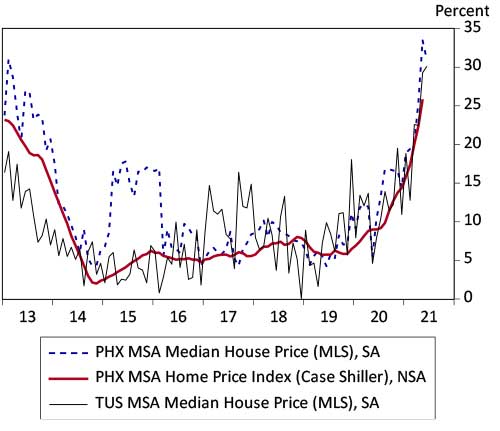

Arizona house prices continued to rise at very rapid rates in June, with the seasonally-adjusted median home price in Phoenix up 31.0% over the year (Exhibit 2). Tucson’s median home price rose 30.1% over the year in June. Median home price gains can be distorted by changes in the mix of homes being sold. The Case-Shiller index measures house price appreciation using repeat sales of single-family homes. The latest data available for Phoenix shows a 25.9% increase over the year in May. Case Shiller does not publish a comparable index for Tucson. The U.S. Case-Shiller index rose 16.6% over the year in May.

Exhibit 2: Arizona Home Prices Are Rising at Very Rapid Rates

Phoenix and Tucson median home prices and the Phoenix Case-Shiller index, over-the-year percent change

Home price appreciation is being driven by a mix of supply and demand-side factors. On the supply side, low inventories of homes for sale are a major contributing factor. Home inventories have been trending down since 2007 and reached new lows during the pandemic. The good news here is that they appear to have stabilized recently and as the pandemic unwinds, they may begin to trend up.

Surging materials prices have had a significant impact on construction costs and new home prices. Over-the-year price increases for construction inputs continue to be strong, but as supply chains return to normal that is expected to gradually ease. Labor shortages will continue to be an issue going forward.

Arizona housing permit activity was very strong through the first half of 2021. Seasonally-adjusted total permits were up 26.4% in the first half of the year, compared to the same period in 2020. Single-family permits drove the increase by rising 41.7% while multi-family permits fell 4.6%.

Phoenix MSA permits increased 27.0% through the first six months of 2021, compared to 2020. Single-family permits increased by 41.9% while multi-family permits increased 1.2%.

Tucson MSA housing permits increased 44.8% through the first six months of 2021, compared to 2020. Single-family permits rose by 51.8% while multi-family permits rose by 8.7%.

While the hot housing market was driven in part by supply-side issues, demand-side factors mattered as well. With the increase in remote work during the pandemic, some workers have more freedom to chose a residential location independent of the location of their employer. It is likely that some of these workers are moving from high-cost metropolitan areas (particularly in the West) to lower-cost locations in Arizona. Compared to many metropolitan areas in the West, Arizona house prices are lower and thus relatively affordable.

Arizona Long-Run Outlook

The long-run outlook for Arizona calls for continued strong growth. The state is forecast to generate job, income, and population gains at a much faster pace than the nation. Phoenix generates rapid gains, well in excess of the nation and faster than the state average. Tucson also grows during the 30-year period, but at a pace close to the national average.

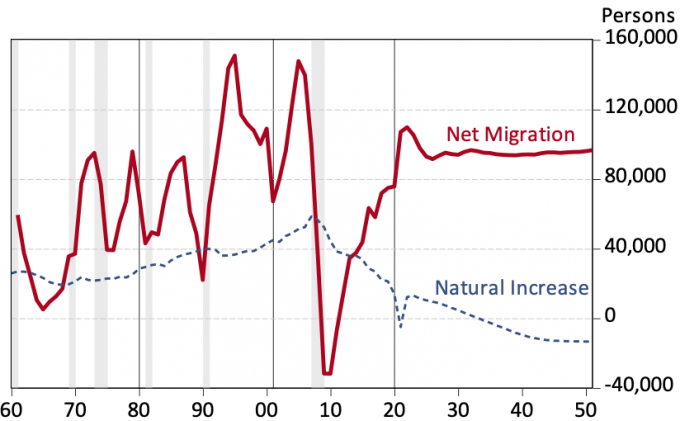

Arizona’s population is projected to reach 10.0 million by 2051, which is an increase of 2.8 million over the 30 year period. That population growth is primarily driven by net migration because natural increase falls during the forecast period (Exhibit 3). Overall, Arizona’s population growth averages 1.1% per year during the next 30 years, well above the expected national rate of 0.4% per year.

Exhibit 3: Net Migration into Arizona Drives Population Growth During the Next 30 Years

Arizona Annual Net Migration and Natural Increase (Births minus Deaths)

Arizona job growth is also forecast to be rapid during the next 30 years, with the state adding 1.5 million jobs (for an annual growth rate of 1.4%). That is well above the expected national rate of 0.6% per year.

During the next 30 years, education and health services; leisure and hospitality; and professional and business services add the most jobs. These three sectors are expected to account for 67.6% of state job gains.

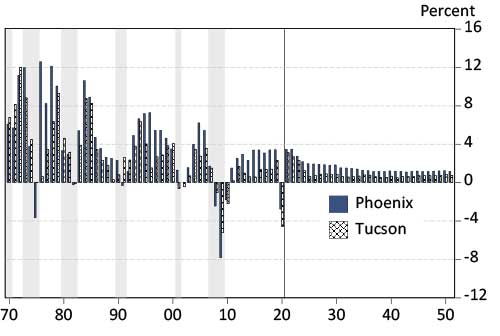

Jobs in Phoenix are forecast to reach 3.4 million by 2051, up 1.2 million during the period. That translates into growth of 1.5% per year, more than double the national pace (Exhibit 9). Tucson is forecast to add 104,000 jobs, with employment reaching 489,000. That translates into growth of 0.8% per year.

Exhibit 4: Phoenix Job Growth Outpaces Tucson, Both Grow Faster than the Nation

Annual Job Growth

Job gains translate into real income gains during the period. Overall, per capita real income for Arizona, Phoenix, and Tucson is forecast to rise at about the national pace during the next 30 years. That implies little or no progress in closing the per capita income gap with the nation.

Risks to the Outlook

The alternative forecast scenarios call for Arizona, Phoenix, and Tucson to continue recovering from the COVID-19 downturn. The difference in the short-run is in the progress in controlling the outbreak.

In the pessimistic scenario, the outbreak fades more slowly than under baseline assumptions, which delays the recovery in travel and tourism and thus the overall economy. In the optimistic scenario, the opposite happens.

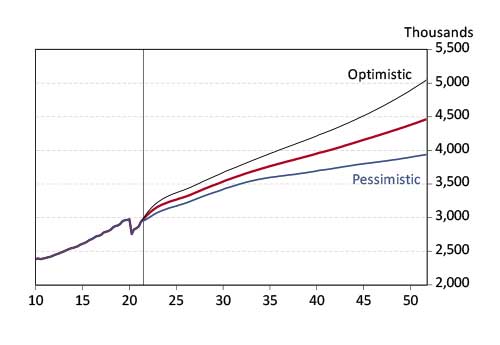

In the long run, the pessimistic scenario assumes slower productivity, labor force, population, and capital stock growth. The optimistic scenario assumes faster growth in the main drivers of long-term growth. Exhibit 5 shows how these different assumptions translate to projections for Arizona employment through 2051.

Exhibit 5: Arizona Adds a Half a Million More Jobs by 2051 in the Optimistic Scenario, Compared to the Baseline

Three Scenarios for Arizona Job Growth

Human capital, typically measured by education attainment, has a significant impact on long-run growth. Arizona has gradually fallen behind many states in the share of its population with a Bachelor’s degree or more. In particular, Arizona (at 29.5%), Phoenix (at 31.7%), and Tucson (at 31.1%) are now below the national average (33.5%) in the share of working-age adults with a Bachelor’s degree or more. It will be difficult for Arizona to make progress in closing its income gap with the nation without improving educational attainment substantially.

Arizona also needs to invest in infrastructure, which ranges from highways, roads, water, sewer, telecommunications, airports, and border ports of entry. It is important to ensure that the state has the infrastructure needed to accommodate growth.

Taxes and regulatory policies matter as well and the state needs to remain competitive with other states on that score.

Climate change is leading to more extreme weather, including heat/cold waves, droughts, and floods. States in the West are struggling with extreme drought and this may impact water prices during the forecast period. While changes in the cost of water are not yet built explicitly into the model, these will be important trends to track in the long-run context.

George W. Hammond, Ph.D., is the director and research professor at the Economic and Business Research Center (EBRC).