The Phoenix Police Department will ban the use of chokeholds on suspects, a change aimed at regaining community trust in the wake of George Floyd’s choking death two weeks ago while he was in Minneapolis police custody.

The decision to end training and use of the “carotid control technique,” a kind of chokehold designed to restrict a suspect’s blood flow, was announced in a tweet Tuesday by the department. The move is effective immediately.

“We can’t function as a department without the trust of our community and there are adjustments we can make to strengthen that trust,” the tweet said, quoting Chief Jeri Williams. “We pride ourselves on being an organization willing to learn and evolve, to listen to our community and become better.”

The Phoenix Law Enforcement Association applauded Williams’ attempt to rebuild trust between police and the community, but said in a statement that there needs to be a “less-lethal” alternative for officers in violent or aggressive situations if the carotid control technique is banned.

“Our members are anxiously awaiting information regarding a replacement for this less-lethal response option,” the statement said.

PLEA President Michael “Britt” London said he understands that the technique seems horrible, but it serves a purpose, if used properly, when dealing with aggressive individuals.

“Really, our concern is like, ‘Hey, you’re kind of taking away a tool and moving us closer to that deadly force option,’” London said Wednesday. “That’s the last thing cops want to do really, is use that.”

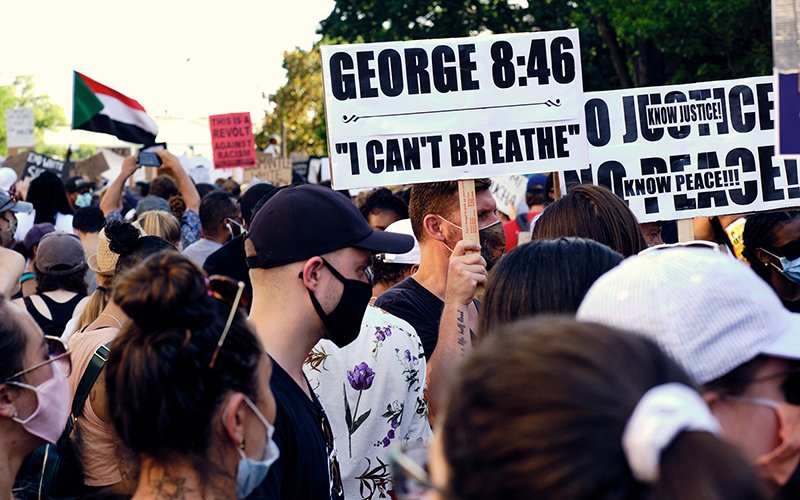

The death of Floyd, 46, sparked nationwide protests after a video showed Minneapolis police officers kneeling on him, with one pressing his knee into Floyd’s neck for almost 9 minutes, despite repeated pleas that he could not breathe. Floyd had been stopped May 25 on suspicion of passing a fake $20 bill, according to news reports, and was not resisting officers in the video.

“I can’t breathe” became a rallying cry across the country, including in Arizona where demonstrators were also protesting the death of Dion Johnson, 28, who was fatally shot by an Arizona state trooper during a traffic stop on May 25 – the same day Floyd was killed. Those protests resulted in several days of clashes with police and a weeklong statewide curfew that ended Monday morning.

Phoenix is not the first police department in the state to have second thoughts about the carotid control technique.

Officer Frank Magos, a spokesman for the Tucson Police Department, said the agency has had a policy prohibiting that kind of hold “for several years.” The Scottsdale Police Department also bans the practice, Sgt. Ben Hoster said.

The Tempe Police Department’s use-of-force policy discourages chokeholds, but says the carotid control technique can be used if an officer perceives an individual’s actions as too dangerous.

The Arizona Peace Officers Standards and Training Board, which sets training standards for police agencies across the state, does not include training in the carotid control technique in its 585-hour basic training curriculum, Executive Director Matthew Giordano said in an email.

Michael Polakowski, an associate professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Public Policy and Government, said the technique restricts blood flow to diminish a suspect’s ability to move. But the technique is dangerous, he said, and should only be applied for a short amount of time.

Polakowski said the prohibition on the chokehold by Phoenix police is a good step, but it needs to be enforced if the department wants to prevent deadly arrests and keep officers from possibly getting away with excessive use of force due to the qualified immunity they enjoy in most legal actions. He said “passing a policy does not necessarily mean that it’s going to change the practice.”

“We need to be able to hold law enforcement accountable for the actions of its officers, and we need to create an environment in which, when something goes wrong, like the Floyd case, the police are held accountable,” Polakowski said.

But London said the PLEA wants to know what officers can use, if not the chokehold, to control violent situations when one side has rules and the other has none.

“We have rules to follow and those people have no rules to follow,” London said. “I don’t know if there’s anything that would be able to replace it. So, that’s why we were kind of wondering if there was something that she (Williams) had in mind.”

Polakowski said banning the chokehold is a first step but that more, broader, action is needed.

“There are a number of things that need to be done. But there has to be a national strategy on the use of force – when different types of force can be applied and in what situations,” Polakoswki said.

“And this can’t be something that’s watered down that people can take pieces from,” he said. “It’s got to be the standard. And people have to be held accountable to it.”

Story by Lisa Diethelm, Cronkite News