The potential health implications of living next to a sewage plant are pretty obvious, but what about living in a neighborhood with no sidewalks? At Arizona State University, Associate Professor Marc Adams is one of the College of Health Solutions’ lead researchers on how a person’s surroundings affect their health. As a member of the International Physical Activity and Environmental Network, he and colleagues recently published a paper in the Annual Review of Public Health about the correlation between built environments and noncommunicable diseases such as cancer, obesity and cardiovascular issues.

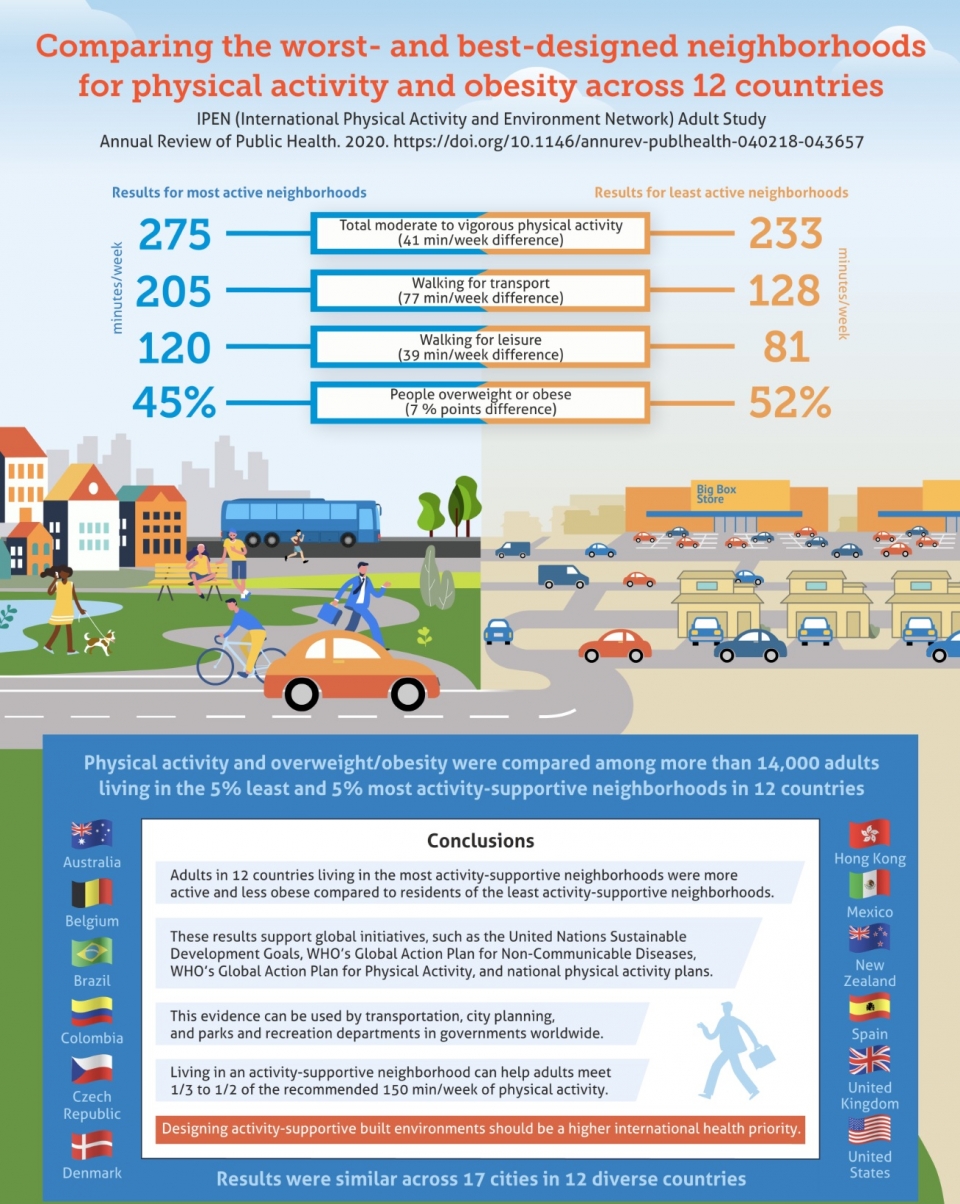

The paper compared physical activity and obesity among 14,000 adults living in the 5% least and 5% most activity-supportive neighborhoods in 12 countries — Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Columbia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hong Kong, Mexico, New Zealand, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States. It concluded that a variety of environmental attributes, rather than a single environmental attribute, is the most effective way to improve population health, especially when it comes to obesity.

So putting a park in a city could theoretically be beneficial to residents’ health, but if there are no sidewalks for them to safely access it, they won’t be able to use it. In other words, it’s better to have both the park and safe sidewalks, Adams explained. And the less variety of built variables, the higher the incidence of obesity in a population.

The study sought to expand on previous research in the field that Adams says was limited because it was mainly conducted in high-income countries where there isn’t a lot of variation in built environments between cities.

“In this study, we wanted to examine the relationship across countries, and get away from that single-country focus to get a better sense of what the true strength of the relationship was between the built environment and physical activity and weight,” he said.

While researchers agreed that a combination of environmental factors is what best contributes to increased physical activity, they also found that anything that can be done to improve the walkability of a neighborhood — such as zebra stripes and stoplights at pedestrian crossings — is a good thing.

“Regardless of where you fall on the continuum of how walkable your neighborhood is, anything that can be done to enhance walkability will have an impact on physical activity,” Adams said.

In addition, he believes increasing residential density is one of the greatest factors associated with higher levels of physical activity in neighborhoods.

“In some ways it seems a little counterintuitive,” he said, “but the idea is that more people can support more shops and services and more infrastructure for walking or cycling. As a result, people are more likely to walk or cycle, and it also means more eyes on the street, which tends to make it feel safer.”

Researchers say designing activity-supportive built environments should be a higher international health priority, and the study’s findings can be used by transportation, city planning and parks and recreation departments in governments worldwide.