About the only person who would disagree about calling the late John F. Long the father of the West Valley would be John F. Long. For more than 60 years, the man described by friends and colleagues as quiet and unassuming, held the vision that transformed the West Valley from fields to thousands of homes for soldiers returning from World War II to emerging cities.

The legacy of John F. Long will live forever,” says Jack Lunsford, president and CEO of WESTMARC. “Unlike footprints in the beach sand, which are eventually washed away, John’s are cast in concrete. And that doesn’t just mean buildings. He left us foresight and philanthropy, all with humility and without fanfare, simply because he loved the area, he loved people, and he wanted to make the West Valley a great place for families to live.”

Long died in February at the age of 87, but his legacy in the West Valley — indeed the entire Valley — will live on, not just in the communities he built, but also in the people whose lives he touched.

“His vision and reality of building a master-planned community is certainly important,” says his son, Jacob Long, who is chief operating officer for the company his father founded, John F. Long Properties. “Not only was he providing an affordable place to live for so many, he was also providing jobs for so many people. A lot of those people not only stayed here, but they are an integral part of helping the West Valley grow as business and community leaders. At least once a week I meet someone who says, ‘Because of your father, my family or I was able to buy a solid home at a great price. It helped me build equity.’ ”

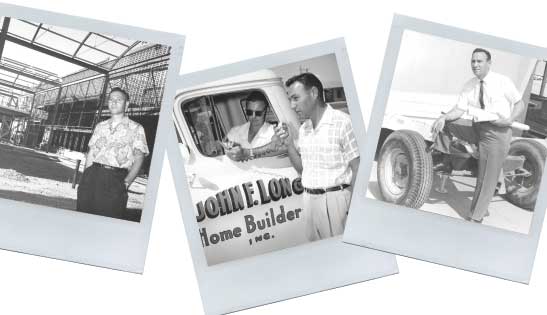

A Phoenix native, John Long got his start in the building industry with a G.I. loan, his own hammer and other tools he borrowed from his stepfather. He first set out to build a home for his new wife, Mary. Instead, he ended up selling the home for twice what it cost to build.

By 1954, John Long was thinking big. He set out not only to build a collection of tract homes in one area, but also to create a community with schools, churches, hospitals, shopping centers and parks. Long created the state’s first master-planned community and named it Maryvale, after his wife.

By applying mass production techniques to homebuilding, Long was able to offer a three-bedroom, two-bath house with a swimming pool for less than $10,000. Houses began selling at a rate of 100 per week, and John F. Long Properties was born.

Despite his success, Long never forgot who he was building the homes for, says Diane McCarthy, director of business partnerships and legislative affairs for West-MEC. For example, when Long first began constructing homes, he realized the VA loans didn’t cover such essentials as refrigerators and stoves. So Long trekked to Washington, D.C., and went before Congress to change the scope of the VA loans.

“He didn’t do it to make money. Making money was a sidebar to what he was doing,” McCarthy says. “He wanted to build communities. He knew with all those returning servicemen after World War II who had served out here either at Williams or Luke, he knew they were going to come West and he wanted an affordable place for them to live.”

Already hailed as an innovator for his assembly line methods of homebuilding, Long adopted sustainable methods years before it became popular. In 1988, John F. Long Homes was chosen by the U.S. Department of Energy to develop, construct and test a demonstration model home featuring roof-mounted photovoltaic solar cells. His Solar One became the world’s first solar subdivision. The 24-home subdivision in Glendale has almost all of its power needs met by ground-mounted photovoltaic cells.

“I think John was probably one of the greatest entrepreneurs and innovators, at least in the housing end, in water conservation, in just general development,” says Rep. John Nelson, (R-Phoenix). “He was a step ahead of everybody in those areas.”

For Long, finding new ways to build homes was just one part of his vision. He was interested in building a community; more specifically, he wanted the West Valley to be a place where people lived and worked. Rather than resent the fact that the West Valley was perpetually in the East Valley’s shadow, Long took the East Valley model and used it to reshape the West Valley. To that end, WESTMARC was born

For Long, finding new ways to build homes was just one part of his vision. He was interested in building a community; more specifically, he wanted the West Valley to be a place where people lived and worked. Rather than resent the fact that the West Valley was perpetually in the East Valley’s shadow, Long took the East Valley model and used it to reshape the West Valley. To that end, WESTMARC was born

“WESTMARC wouldn’t have happened without him. It’s just that simple,” says McCarthy, who first met Long in 1992, when she became the first director of WESTMARC. “He provided a lot of the seed money for us to get started, and in addition to the money, he talked to a lot of people. When you’re starting up an organization like that, you don’t have a lot of credibility because you don’t have a track record. He was willing to talk to other people and say, ‘Look, I really believe in what this organization can do and we have to give it a chance. And we all have to be willing to roll up our sleeves and get involved and help make a lot of these things happen.’ ”

Making things happen was a John Long specialty. He was always quick to donate money, land or services to make sure his beloved West Valley would continue to grow and be a place where people could raise families and build communities. A very small portion of what he gave includes the labor and material to fill potholes on 550 miles of West Phoenix streets; building and donating 21 townhouses to the city’s Affordable Housing Program; and when the Milwaukee Brewers were looking for a new Spring Training home, donating 60 acres of land for the Maryvale Baseball Park – as well as lending the city $10 million for construction.

Besides giving out of his own pocket, Long made sure others with the wherewithal gave as well.

“Dad was born and raised in Phoenix,” Jacob Long says. “This makes a huge difference. You have that sense of ownership and pride. He always was looking for ways to help others help themselves, who in turn might have the same feelings and be inspired. That is how true communities flourish.”

John Long had a standing challenge to other developers who built in the West Valley, Nelson says.

“He’d say, ‘I’ll do this if you do that,’ ” Nelson adds. “If you took a look at the developers who took a project on the West Side, they always had that challenge with John to put a project in pace that had benefits for those who lived there.”

McCarthy recalls a time when the library and senior center just north of Indian School Road and 51st Avenue badly needed repairs. Long made sure money for the upgrades was included in a bond measure. The measure succeeded, but when he found out the renovations weren’t scheduled until years later, Long took matters into his own hands.

“He went to the city and said, ‘Here’s the check for $10 million. Get it done sooner and pay me when the bond proceeds come in,’ ” McCarthy says. “So that beautiful, beautiful library and senior center he lived to see done.”

Exactly how much Long gave to the community is not exactly known, as most of his work was done behind the scenes and with no fanfare.

“Both parents instilled in us the need to be aware of someone who truly needs help and is experiencing a tough time through no fault of their own,” Jacob Long says. “One such person, a teenager, experienced a very bad athletic accident. He was confined to a wheelchair and his parents didn’t have the resources to modify their home. Dad read about this in the newspaper and he contacted the family and offered to remodel their home to accommodate the son’s special needs. This way he could be with his family. No one asked (my Dad) to do this.”

His philanthropy was not a recent development. In fact, he established the John F. Long Foundation, a nonprofit group supporting local charities, schools, education events and general community needs, in 1959. Long was generous in the extreme, but he was still a businessman and he would fight to protect his interests and those of the community he loved.

“He had a heart of gold and was tough as nails when he had to be,” Nelson says. “John sued the living daylights out of the city of Phoenix (in 1986) because they sold water to Palo Verde (Nuclear Generating Station). That was another side of John; he was not afraid to fight. If he felt he was right, he’d drag you to court. He didn’t care who you were.”

In 2000, WESTMARC created a lifetime achievement award and named it after Long. Despite all of his years working for the West Valley, the honor came as a surprise to him, McCarthy says.

“We told him we named it after him and I had never seen him speechless up to that point,” she says. “He was so thrilled at that. And then every year, I would take a couple of names to him and ask him, ‘Who do you think should get it?’ And he’d pick out the one and say, ‘That’s the one.’

“He never, ever flaunted anything. He was the most humble person. He would walk into a room and quietly sit down and unless you knew John Long, you wouldn’t know it was him,” McCarthy says. “I miss him. He was always somebody to call if you had an idea and he was willing to call you if he had an idea. And that’s how things get done.”