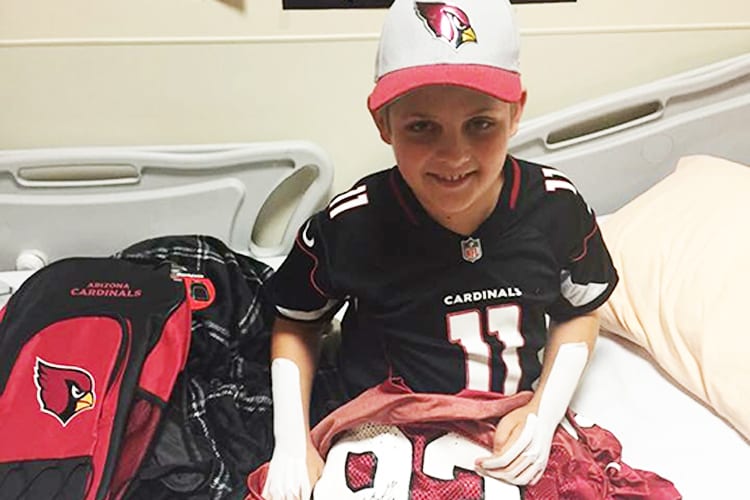

Talen Spitzer was a healthy 10-year-old kid from Queen Creek a little more than two years ago when, in a matter of minutes, he lost control of his muscles and his hands were paralyzed.

His mother, Rochelle Spitzer, said doctors did not know what was wrong with him at first because everything else seemed normal. But when scans at the hospital later showed lesions on his spine, he was diagnosed with acute flaccid myelitis, an extremely rare polio-like “mystery disease.”

Talen was one of eight patients in Arizona since 2014 who have been confirmed victims of the disease, which has no known cause.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this week said it has confirmed a total of 386 cases of the disease, known as AFM, in at least 38 states and the District of Columbia since 2014, when it first surfaced in the Midwest. There have been 62 cases confirmed in 22 states so far this year, the CDC said.

The disease primarily affects the young, causing weakness in muscles and paralysis in the lower limbs that eventually start rising toward the chest, according to Dr. Sean Elliott, professor of pediatrics at University of Arizona.

“They (patients) many times are not able to walk, they are unable to move onto legs very effectively, many are unable to even talk effectively,” Elliott said. “The worst patients have had difficulty in breathing because, of course, we breathe using muscles as well.”

Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said in a conference call Tuesday that AFM is a fairly new disease and that there is still a lot to learn about it.

Scientists do not know what causes it, how it spreads or even its long-term effects, Messonier said, according to a transcript of the call. They know it is not caused by the polio virus, even though its victims suffer polio-like symptoms, but that it has been linked to other viruses, including West Nile and enterovirus, and environmental factors.

Researchers do know that rates spike in the fall and that more than 90 percent of cases are in children 18 or younger. But Messonier said she is “frustrated that despite all of our efforts,” researchers have not been able to find a cause.

Despite that, she said there are simple steps parents can take to protect their kids, including making sure children wash their hands, use bug spray and stay up to date on their vaccines.

She also urged “parents to seek medical care right away if you or your child develop sudden weakness or loss of muscle tone in the arms or legs.”

Recovery is mixed. Elliot said there’s no specific treatment for the disease, and that many patients recover spontaneously. The ones who don’t “have a long road ahead of them with physical therapy, rehab,” he said.

Messonier said she only knows of one patient who had AFM and died in 2017. But Elliott said it appears that patients can die of complications caused by it and not the disease itself.

“If one is unable to breathe and does not get medical care, then yes, the death is due to respiratory failure,” he said. “The illness itself … seems to not cause death.”

During the worse part of his disease, Talen was prescribed with steroids and started undergoing physical therapy seven times a week.

“There’s absolutely no way he would have been able to recover without therapy,” Rochelle Spitzer said.

Talen just turned 13 and is able to run and play soccer, although he still has some limitations like struggling to tie his shoes, Spitzer said.

Messonier said AFM is extremely rare, affecting fewer than one person in a million. But Spitzer said it is important to raise awareness: She knows of another Arizona family with a child who’s been diagnosed, and believes the condition is a lot “more common than it seems.”

Messonnier said that she understands “what it is like to be scared for your child. Parents need to know that AFM is very rare, even with the increase in cases that we are seeing now.”

Elliott said parents should alert, but should keep it in perspective.

“It’s new. It’s scary. It’s a significant disease, but in terms of true national threat from infectious disease, of course, influenza, the flu season is far greater. There were 80,000 deaths from the flu last season in the United States,” Elliott said.

Story by RENATA CLÓ, Cronkite News