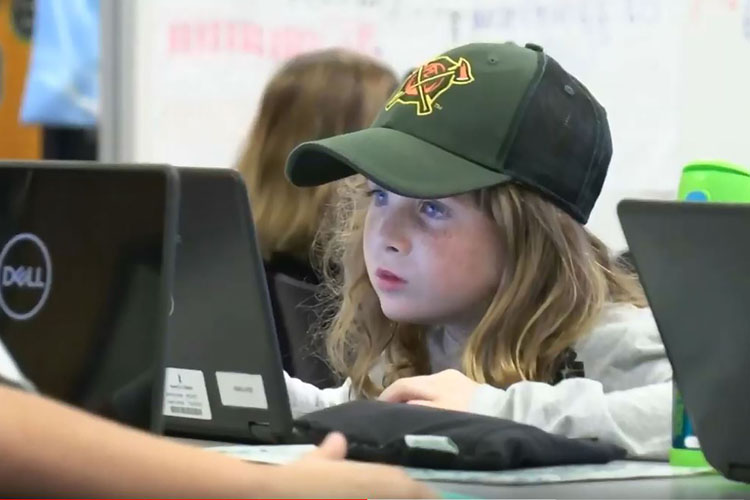

Students in grades K through 12 have no memory of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Twenty years after that pivotal event, educators are having to find ways to teach 9/11 to the next generation.

Many teaching resources are available from the National Education Association, The New York Times, NPR and other sources, but how can teachers help a generation of students connect to a devastating event that rocked our national conscience and instantly changed the way Americans live?

Chris Raso has been teaching social studies at Canyon Ridge School in the Dysart Unified School District in Surprise for 15 years, and every year has held a 9/11 commemoration assembly for students in grades 5 through 8. The assembly features Andy Simoneschi, a former first responder who’s now the school nurse at Canyon Ridge, talks about his time at Ground Zero, where two hijacked planes crashed into the twin-towered World Trade Center in New York City.

READ ALSO: Nonprofits will mark 20th anniversary of 9/11 with national day of service

“He goes on firsthand accounts of the students and also gives an inspirational message to all,” Raso said. “We’re allowing students an outlet for their learning, for their feelings and questions about the event because our students now have no recollection of this.”

This year, the students are putting together a collage of photographs, newspaper articles and written responses that have been collected over the past 10 years to give as a gift to “Nurse Andy.” Students in multiple grade levels are also going to read articles and journal excerpts from rescue workers on 9/11.

Raso said they also make sure to teach compassion in addition to patriotism.

“We always have elements of how we should treat other groups of people, or how we should treat individuals based on this or that because, as always, it’s an opportunity for character education,” Raso said. “We always incorporate how important it is not to blame an entire group of people for a particular event and not to add doubt or violence or judgement of others.”

Organization focuses lesson plans on the Sikh experience

The Sikh Coalition, which formed in New York in response to 9/11, worked with the University of Pennsylvania to create a set of lesson plans called Teaching Beyond September 11th. This curricula helps educators teach about the events of 9/11 with emphasized modules on the Sikh American experience or those who practice the Sikh religion.

This free curriculum for high school and undergraduate students also looks at the ongoing global impact of 9/11 while also exploring social justice, representation, solidarity, public opinion, democracy, and U.S. foreign and domestic policy, according to the Sikh Coalition website.

Pritpal Kaur is the education director for the Sikh Coalition and helps to create and review educational content about the Sikh community. She said a lot of educators look at teaching 9/11 as having a courageous conversation.

“Every student that you will have been teaching now will have grown up in a post-9/11 world, and everyone’s experience of that will have been totally different,” she said, noting that the 9/11 lesson plans explore “the impact that 9/11 had on various religious communities and South Asian communities in the aftermath – and it’s been ongoing for the last 20 years.”

The first module of Teaching Beyond September 11th focuses on how hate toward the Sikh community only escalated post-9/11. The second allows students to explore the idea of conflicted identity along with themes of Islamophobia and breaking down the stereotype of what a terrorist looks like.

One of the first victims of 9/11-induced hate toward Sikhs was Balbir Singh Sodhi, 49, an Indian immigrant who was gunned down outside his Mesa gas station by a man who assumed he was Arab. Frank Roque is serving a life sentence for the murder, which was committed four days after 9/11.

The curriculum was released earlier this month, but educators are already interested.

“We had teachers and educators that want to learn more about how to teach about South Asian American communities in their classrooms and how to address these new waves of anti-Asian hate that we’ve been seeing,” she said. “This kind of material will really open up those courageous conversations and prepare (students) for the diversity and some of the issues that are important to understand.”

Not all Arizona schools have 9/11 curriculum

Many schools in Arizona don’t have an exact curriculum on 9/11 and instead focus on 9/11-related social studies or include it as an example in another lesson.

“Arizona is a local control state and does not dictate the exact curriculum or instructional methods educators use to teach state standards,” Morgan Dick, spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Education, said in an email.

Phoenix Union High School District includes terrorism education and 9/11 in its curriculum, spokesperson Richard Franco said. The district plans to recognize the 20th anniversary of the attacks and ask teachers to talk to students about 9/11.

Another way students are learning more about 9/11 is through museum exhibits and guided tours. Mark Moorhead is the curator of education at the Hall of Flame Museum of Firefighting in Phoenix, which touts itself as one of the largest historical firefighting museums in the world.

Along with teaching the history and technology of firefighting, the museum also highlights the people who gave their lives in catastrophic events like the firefighters of 9/11.

He said he wants people to remember 9/11 with proper context and to never forget those who sacrificed themselves for public service. The museum houses the Rescue 4 fire engine that was used by the New York City Fire Department on 9/11.

It also highlights the firefighters who died while on duty in New York in its “Hall of Heroes” exhibit with the names, companies and photographs of the 343 FDNY firefighters and others killed in the attacks. The gallery also has a full-size decorated model of a quarter horse to honor the firefighters and police officers donated by the Trail of Painted Ponies project in 2004.

“We think it’s very essential, and we try to tell the story honestly but to also remind kids of the heroism, which makes it not just a scary and terrible and heartbreakingly bad day but also an inspirational day as well,” he said. “It gives us more of a human face to the name of those lost.”