National wildlife refuges in Arizona add millions of dollars to the state economy each year, according to a recent study by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

“The national wildlife refuges provide wildlife habitat and places for people to hunt, fish, bird watch, canoe [or] kayak, view and photograph wildlife and connect with nature,” said Tom Cadden, who represents the Arizona Game and Fish Department. “Studies show that people who are connected to nature enjoy health, learning and lifestyle benefits. The refuges can also benefit local economies as a draw for tourism.”

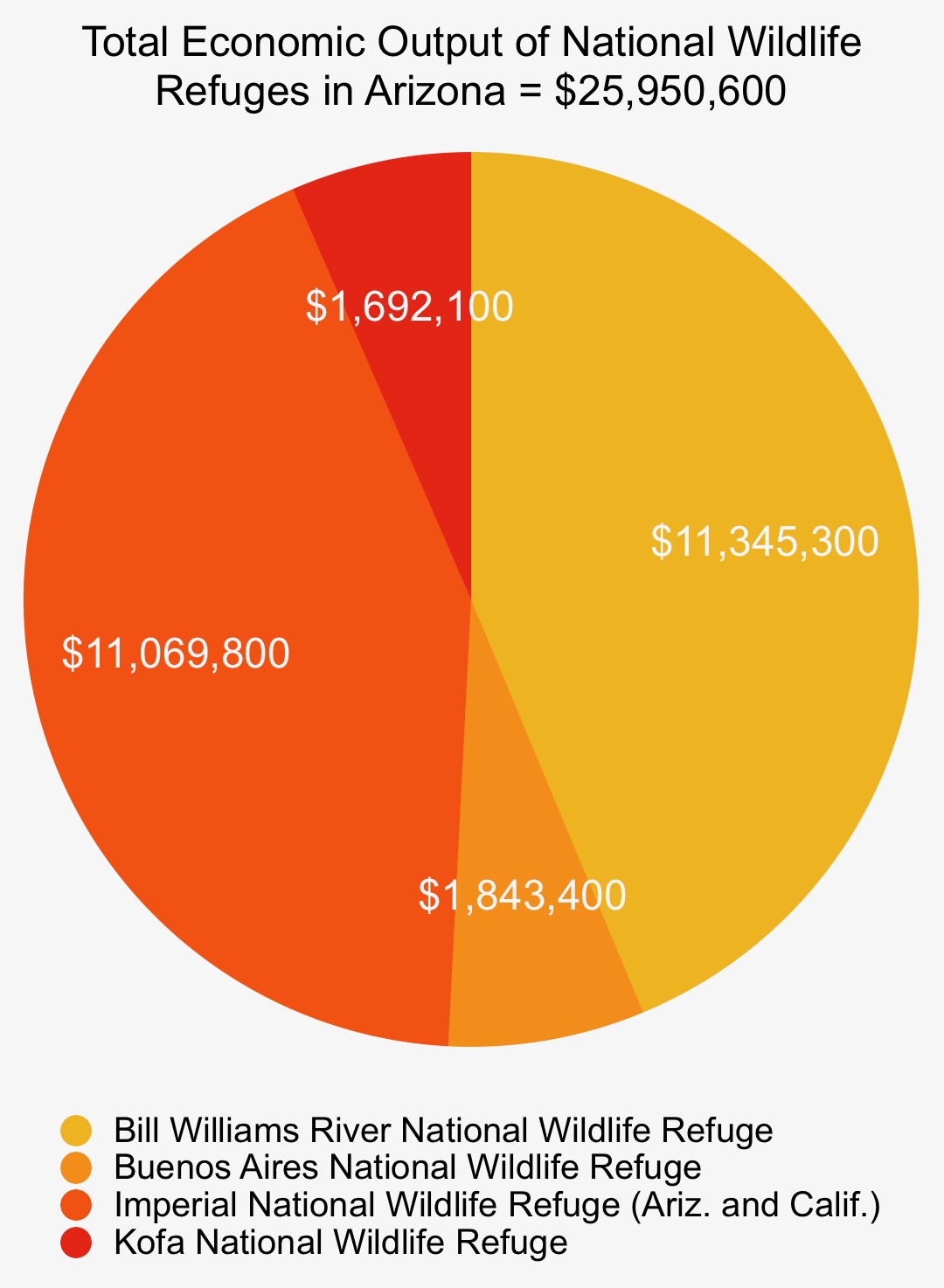

Four of Arizona’s nine wildlife refuges were included in the national study: Bill Williams River National Wildlife Refuge in Lake Havasu City; Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, near the U.S.-Mexico border; Kofa National Wildlife Refuge, northeast of Yuma; and Imperial National Wildlife Refuge, which sits on the Arizona-California border north of Yuma.

“While Arizona’s national wildlife refuges account for only a tiny fraction of the 45 million travelers who visit our state each year, these well-preserved wild places mean a great deal to our travel brand,” said Scott Dunn, senior director of content and communications for the Arizona Office of Tourism. “Year after year, our consumer research finds that outdoor recreation is one of Arizona’s top drivers of tourism.”

In individual economic reports, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said each refuge “provides a variety of environmental and natural resource goods and services,” which result in economic effects for both local and state governments.

“Having a nearby opportunity to recreate and enjoy wildlife and the natural setting associated with most refuges enhances the quality of life for those living in the community,” Cadden said. “Refuges can also contribute to the community’s brand when trying to attract tourists.”

More tourists means more economic benefit, but it is important to also note the additional statewide economic benefits beyond the refuges themselves, Cadden said.

“Hunters, anglers and wildlife viewers spend about $2 billion annually in Arizona in trip-related and equipment expenditures,” he said, referring to a survey showing the most recentdata on wildlife recreation.

The Fish and Wildlife Service groups the benefits provided by refuges into five categories: (1) maintenance and conservation of environmental resources; (2) protection of natural resources including fish, wildlife and plants; (3) protection of cultural and historical sites; (4) educational and research opportunities; and (5) outdoor and wildlife-related recreation.

“Arizona’s refuges offer some of the best wildlife viewing and birding not just in the state but in the country,” Dunn said. “Many of them are also paradises for sportsmen and sportswomen, with opportunities to hunt and fish in rugged areas that are much less trafficked than national parks and recreation areas.”

Bill Williams River National Wildlife Refuge, on the western edge of Arizona, was established in 1941 as part of the Havasu Lake National Wildlife Refuge, but it split off as its own refuge in 1993 due to its “uniqueness and diversity of habitat,” according to the refuge’s economic report from the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Bill Williams River now sees about 326,000 total visitors each year, more than one-third of whom are from out-of-state. The refuge has an annual economic output of $11.3 million, creating 113 jobs and nearly $1 million in annual tax revenue for state and local governments.

“This lush riparian habitat in the desert attracts a variety of neotropical migratory bird species, as well as many resident species, to the tune of over 350 species,” the report reads. “This makes the Refuge one of the most avian-diverse of all the refuges in the United States.”

Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge takes up about 118,000 acres near the Arizona-Mexico border, with elevations ranging from 3,200 to 4,800 feet. The refuge, home to reintroduced pronghorns and the endangered masked bobwhite quail, has seen nearly 340 unique species of birds, drawing bird watchers from across the U.S.

“The mix of grassland, riparian, and mountain stream habitats attracts many subtropical bird species,” according to the Fish and Wildlife Service economic report. “The grasslands and the rugged mountains nearby have yielded reports and photographs of the occasional jaguar wandering north from Mexico. The variety of wildlife and rarities such as the jaguar attest to the importance of protecting this area for natural values.”

Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge sees more than 55,000 visitors annually, creates more than $1.8 million in economic output and fetches $130,000 in annual tax revenue for state and local governments.

Kofa National Wildlife Refuge surrounds the Kofa Mountains in the southwestern corner of Arizona, and the mountain range’s summit, Signal Peak, stands 4,877 feet tall. The driest part of the Sonoran desert makes up more than 80 percent of the refuge, which was created to protect desert bighorn sheep and other native wildlife and their habitat.

Kofa takes its name from the King of Arizona (KOFA) Mine, the largest gold producer in the Lower Colorado Basin at the turn of the 20th century, according to a brochure from the Office of Tourism.

“Today, the area offers a wealth of opportunity for hikers — and a chance to view resident bighorn sheep, mule deer, fox and a wide variety of birds and burrowing critters,” the brochure said.

Visitors may also catch a glimpse of endangered Sonoran pronghorn that are being reintroduced to the area, according to the economic report by the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Kofa sees more than 95,000 visitors annually, 75 percent of whom are Arizona residents. The refuge has a total annual economic output of nearly $1.7 million and brings in $117,000 in state and local tax revenue.

Imperial National Wildlife Refuge is a 31,303-acre area spanning the border of Arizona and California along the Colorado River, behind Imperial Dam.

“The river and its associated backwater lakes and wetlands are a green oasis, contrasting with the surrounding desert mountains,” the Fish and Wildlife Service said in its economic report. “This portion of the river includes the last un-channelized section before its waters enter Mexico.”

One of the larger refuges of the four studied, Imperial sees more than 274,000 visitors annually, who visit for the scenery, hiking and fishing opportunities. The refuge has an annual economic output of more than $11 million, employs 100 people and garners almost $1.1 million in state and local tax revenue, bringing the grand total of tax revenue from these four refuges to about $2.3 million.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service does a good job of protecting refuges, but the refuges should be widely accessible to the public for a full suite of compatible outdoor-related recreation, including hunting, fishing and wildlife viewing,” Cadden said. “Support for the refuge system depends on the public valuing refuges as places that not only provide wildlife habitat, but also as places where they can participate in a variety of wildlife and nature-related recreation.”

Visitors can help protect refuges by acting responsibly and treating the land with respect, he said.

“Our rugged and beautiful Southwestern landscape is a differentiator when it comes to influencing visitor behavior,” Dunn said. “The state’s nine national wildlife refuges — just like its 22 national parks and monuments, six national forests, 35 state parks and 22 sovereign American Indian communities — help define our global travel brand as a premier place to spend time outdoors.”

This story was originally published at Chamber Business News.