For the first time in Arizona, work by Leonardo da Vinci is being displayed in a new exhibition focused on his manuscript “Codex Leicester” at the Phoenix Art Museum. Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester and the Power of Observation centers around the presentation of the “Codex Leicester,” a manuscript Leonardo (pronounced Lay-oh-nar-doh) — his full name; da Vinci only referrs to his birthplace of Vinci — filled with notes, thoughts and observations about nature, astronomy and technology. Displayed separately in stand-alone cases in the middle of a cavernous room, the 18 pages of the manuscript pull the entire exhibition together, tying in the additional 31 works within the exhibition.

With a main exhibit being a manuscript written in sixteenth century Italian, the challenge was to make the exhibition accessible and relevant to people today, said Jerry Smith, curator of American and European art to 1950 and art of the American West for the museum.

The “Codex Leicester,” which covers topics from gravity and astronomy to erosion and water control, has pages covered almost entirely with Leonardo’s thoughts, showing a linear thinking pattern, until he comes back to a page to write a note in the corner or margin. That jumping around makes it clear that Leonardo was trying to work out problems; he didn’t always know the answer as he was writing.

Drawings line most of the pages margins, whether doodles of planets or sketches of waves. The planets are almost always perfect circles, and the waves, as pointed out by Smith, show very similar strokes as “Mona Lisa’s” hair.

To make the codex relevant and understandable, the curators chose art on similar scientific topics to accompany the “Codex Leicester” in the exhibition. Opposite pages on Leonardo’s observations of water are Harold Edgerton’s famous photos of drops of water, movement frozen in time.

The next wall features two paintings by Monet showing a different and more modern expression of observing nature. One of the paintings, “The Cliff, Étretat, Sunset” features a sunset that astrophysicists have been able to pinpoint the exact moment in time that Monet painted. That mixture between art and science is what the exhibition was aiming for.

Other works include photographs by Ansel Adams, a series of motion sequence photographs of running horses and one of the first aerial views of a European city, Jacopo de’ Barbari’s “View of Venice.” Seen as a whole, the exhibition ties together several centuries and disciplines using “Codex Leicester” as the common theme.

Heard in intervals throughout the exhibition, Bill Viola’s “The Raft” is in a room to itself, but not to be missed. At just over 10 minutes, the video extends what took 60 seconds to record, stretching out the action to almost painfully slow speed. It shows yet another form of modern observation, and what Leonardo might have done had he had a camera, Smith said.

Despite being the painter of one of most famous works of art in the world, Leonardo was never published in his lifetime. Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester and the Power of Observation shows just why the work by Leonardo’s own hand is one of the most important intellectual documents of all time.

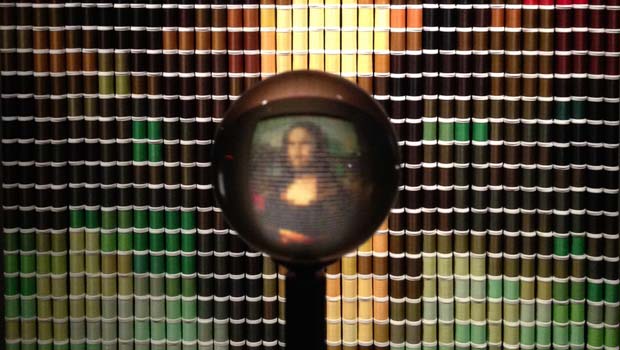

Exhibits also include work by Gustave Courbet, Kiki Smith, Eadweard Muybridge, Edward Weston, Andreas Feininger, Tony Foster and Devorah Sperber. The exhibition will be at the Phoenix Art Museum until April 12.