Blonde is torture. Not for the viewer, necessarily—though your mileage may vary—but for Marilyn Monroe, whose life the film distills into a series of tragedies. Marilyn (born Norma Jeane) was by many accounts a troubled person, but she was also a hardworking woman who, among other successes, founded a production company that helped contribute to the fall of Hollywood’s studio system. You’d never know that from Blonde, which is more a cavalcade of brutality than a biography.

But Blonde isn’t meant to be a biography. Based on Joyce Carol Oates’ novel of the same name, it’s a semi-fictional story that parallels its distance from reality with Norma Jeane’s distance from the Marilyn persona. By implicitly acknowledging that it’s not depicting the real Marilyn, Blonde allows the woman her human inscrutability, and in dramatizing versions of what she faced, the film weaves a vicarious tapestry of her context, sketching her silhouette by filling out the negative space. The film isn’t forward about this artistic conceit, but it doesn’t need to be—the Internet is your artwork label.

READ ALSO: Read more movie reviews here

It’s at the very least arguable that Andrew Dominik, Blonde’s writer/director, uses biographical fiction as a means of exploitation. The camera watches Marilyn’s body—Ana de Armas’ body, if you strip away the layers of persona—almost lasciviously, echoing the eyes of the men who abused her culturally, financially, and literally. Blonde’s depiction of the famous subway grate scene, where throngs of onlookers gathered to watch Marilyn’s skirt blow up, is leery in gaze and sinister in tone, distorted by slow motion and the chilling, mournful score from Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. The film stares, disgusted by itself and everyone doing the same. The only line between experiment and exploitation is metatext—which has a habit of collapsing in on itself.

On top of, for example, de Armas looking directly at the camera and asking, in character, “What business of yours is my life?”, the vulgar experiments feel belabored. Why push the boundaries of self-reflexive commentary on femininity, fame, and exploitation if you’re just going to spell it out like that? Are Dominik’s provocations just a different kind of low-hanging fruit? Maybe.

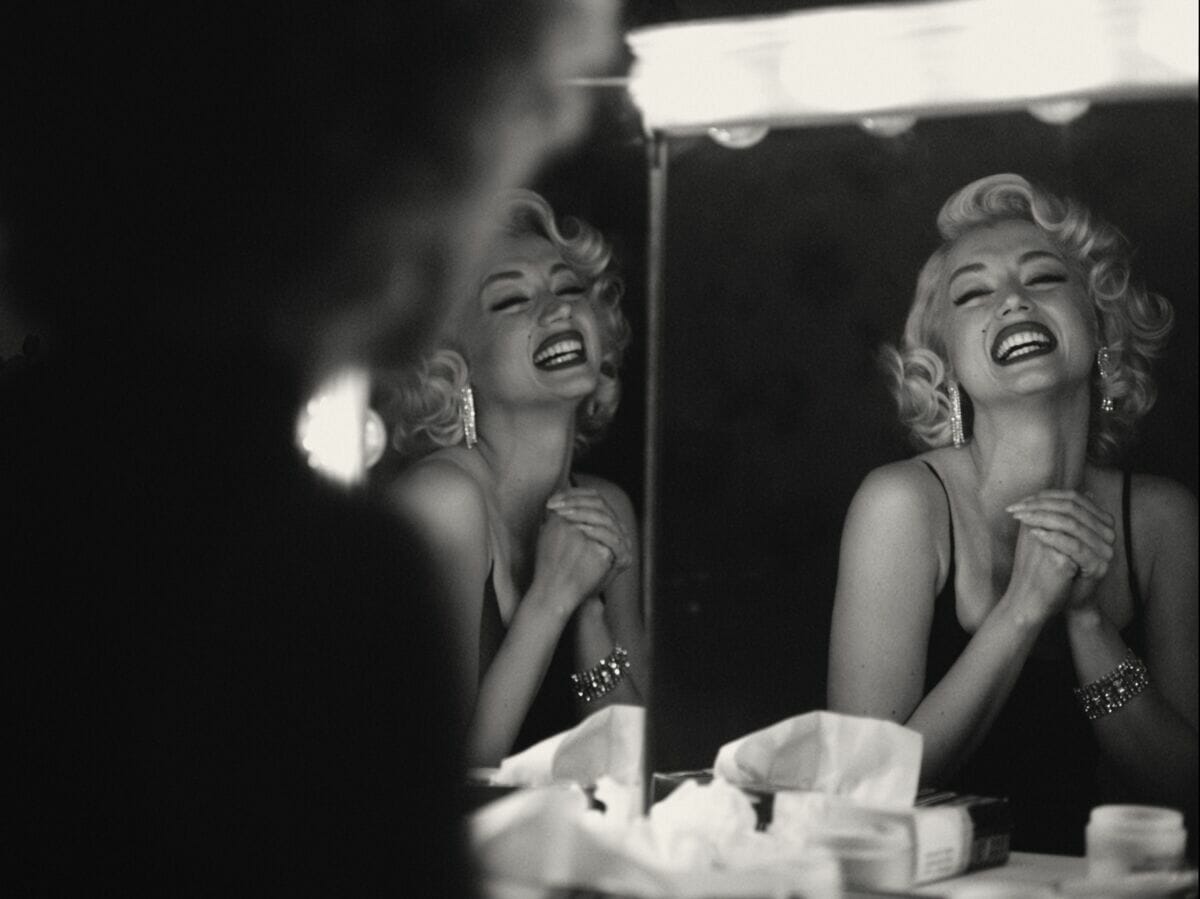

The translation to screen certainly dulls subtleties of Oates’ novel. One formative scene, in which a producer rapes Monroe during one of her first auditions, is on the page conveyed entirely by Marilyn’s inner monologue, but in the film, it’s a graphic, on-screen assault with barely a word from her. The length and limits of literature were good for Blonde; in the much-condensed film, shock and trauma are visual shorthand. Moreover, the presence of an actress playing the woman with an actress persona is a little over the top for this meta-biography. It’s a performance of curated artifice—it always feels like “Ana de Armas as Marilyn Monroe,” which fits the subtext but further abstracts the subject. Perhaps Dominik saw bluntness as a way out of abstraction.

What’s thematically blunt is aesthetically potent, however. The film cuts between points in time—and between reality and metaphor—with a fluid, free-form motion that melds all of Marilyn’s pain into a menacing mood piece. VFX stretches men’s faces into ogling, inhuman abominations; lighting changes contort Hollywood’s glory into its dark underbelly; sound design puts us inside Marilyn’s head; and the gloomy, ominous score portends a world that will never stop using her. Not every choice is powerful—the film alternates between color and black-and-white so often that it starts to feel arbitrary—but the cumulative effect hits hard. It’s surrogate dehumanization, and if it doesn’t empathize, it at least understands.

Does Blonde understand Norma Jeane, the woman behind all the myth and metaphor, the way it understands the meanings it can make from her? No, and it’s not particularly interested to.

★★★ (3/5)